The Switch to Solar at Coal Power Plants and Mines is On

Project developers, investors, government and community organizations in the U.S. are coming together to resolve the socioeconomic and environmental issues associated with deploying solar energy-fueled power systems at former coal power plants and mines, thereby hastening the transition from fossil fuel to emissions-free, renewable energy resources.

Located amid some of the most iconic geography in the U.S., the 2.25-gigawatt (GW) Navajo Generating Station (NGS) and Kayenta coal mine near Page, Arizona have been providing electricity that has fueled the development and growth of cities and towns across the southwestern U.S., as well as creating hundreds of much needed, highly valued jobs for residents of the Native American Navajo Nation. Successive efforts by the plant and mine’s owners and a last-ditch vote by the Navajo Nation Council to keep the coal mine and power plant up and running have failed. Now, a member of the Council, supported by local activists, proposes to revise and update the tribal Native American nation’s energy policy so that it’s centered on community-centered development of abundant solar and other renewable energy resources.

Some 3,120 kilometers (~1,940 miles) east, coal has been at the center of the economy and society across the Appalachia region since the dawn of the U.S. Industrial Age. Owners have been shutting down the region’s coal mines over the course of recent decades as they’ve become uneconomical to continue operating, however. That has created a vacuum in terms of well-paying jobs and economic opportunities in surrounding communities.

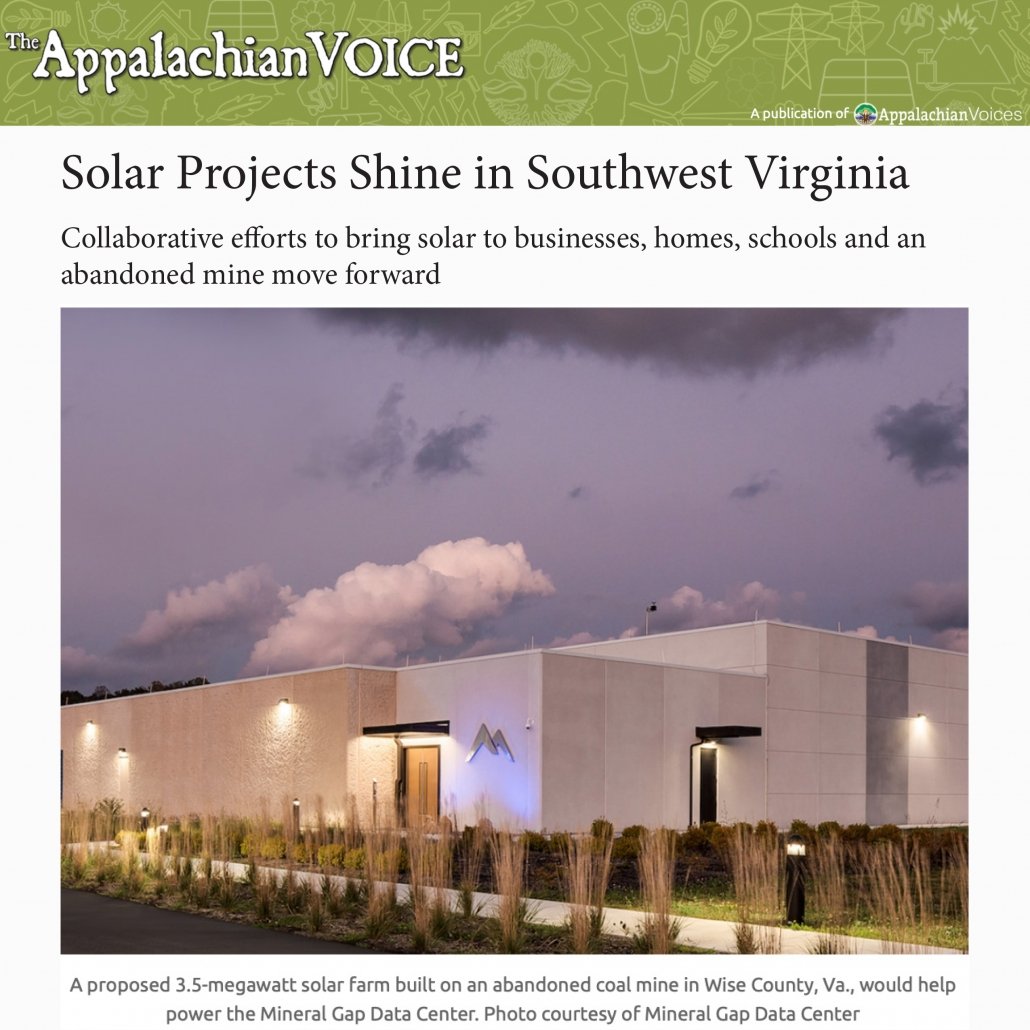

Solar power project developer Sun Tribe Solar and Mineral Gap Data Centers, working closely with local, state and federal government and community organizations, aims to revive and energize an area of southwestern Virginia by deploying a 3.5-megawatt DC (MWdc) solar power farm on the site of an abandoned coal mine in Wise County that was last mined in 1957. If successful, the project will be the first to convert an abandoned mine to a solar power farm under the federal, state and local government Abandoned Mine Land Pilot Program (AML), the aim of which is to reclaim mine lands and boost economies throughout Appalachia.

The most reasonable thing to do

The Navajo Nation Council voting down a last-ditch effort to purchase and keep the Navajo Generating Station on March 21 marks the end of an era. Barring any further developments, the power plant will be shuttered Dec. 22.

The largest coal-fired power plant in the U.S. West, the Native American Tribal Council government has been able to rely on the electricity produced by the plant and Kayenta coal mine for revenues and steady, well-paying jobs since the mid-1970s, two benefits that have long been in short supply on the Native American reservation for decades.

A record of 15.4 GW of a nationwide total of 260 GW of coal-fired power generation capacity is expected to be retired in the U.S. in 2018. That’s expected to rise to 36 GW or more by 2024 despite efforts by the Trump administration to revive coal mining and power.

It’s economics, as opposed to political pressure or state renewable energy mandates, that’s fueling the trend, according to a recently released study from Energy Innovation. It would be cheaper to replace just shy of three-quarters (74%) of the U.S. fleet of coal power plants with solar or wind power, according to Energy Innovation’s analysis.

Immediately following the “no” vote, Navajo Council legislator, Elmer Begay, introduced a bill to “move the Navajo Nation beyond coal source revenues and forward to sustainable, renewable energy sources.” The bill proposes the creation of a transition task force by June 7 that would be charged with providing recommendations regarding ways and means of replacing the jobs and revenues lost from the closure of the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta Mine, as well as ways and means of providing assistance to workers who lose their jobs.

“The most reasonable thing to do is to put solar energy on the transmission line and own it and operate it,” Nicole Horseherder, executive director of the nonprofit water resources conservation and clean energy development group Tó Nizhóní Ání (TNA, or Sacred Water Speaks), was quoted in an industry news report.

Tó Nizhóní Ání’s primary concerns and activities revolve around water resources protection and conservation. That has drawn it into discussions and debates regarding the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta mine, both of which have huge impacts on the water resources and ecosystems of the Navajo and neighboring Hopi.

Advocating for Navajo solar since 2003

TNA has been advocating for investment in and locally-centered development of the Navajo Nation’s solar and other renewable energy resources since way back in 2003. At that time the organization began discussing solar energy development with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) being one of what were five owners of the Navajo Generating Station at the time, Horseherder recounted in an interview.

One of NGS’s owners is the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees water resource management nationwide; more specifically as it applies to oversight and operation of diversion, delivery, and storage projects, it has built throughout the western U.S. The U.S. agency is the largest wholesaler of water in the nation, delivering water to more than 31 million people and providing one in five Western farmers with irrigation water for 10 million acres of farmland which produce 60% of the vegetables and 25% of the fruits and nuts grown nationwide. In addition, the USBR is the U.S.’ second largest hydroelectric power producer. All that results in a conflict of interest regarding the USBR’s role as an owner of NGS, Horseherder pointed out.

TNA since 2013 has been campaigning against the Navajo Nation buying, or participating in the purchase of, the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta coal mine and keeping them running due to concerns about the negative human health and environmental, as well as economic, effects. These include depletion of the area’s groundwater aquifer, the sole source of drinking water for surrounding communities, as well as the coal mine’s water usage and rising groundwater contamination in the surrounding area, Horseherder explained.

The prospect of using scarce capital to acquire an uneconomical coal mine and power plant also figured prominently in TNA’s arguments. Added to that were the unknown costs of environmental remediation of the site and other, prospective liabilities when it is shut down, Horseherder said.

Nuclear figures into the energy mix on the Navajo Nation as well. Nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted from Navajo lands under leases with the Navajo Nation from 1944 to 1986, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Five federal agencies are working together to reduce the highest risks to Navajo people from uranium contamination resulting from the abandoned mines.

TNA is totally against nuclear and firmly believes that solar energy and the combination of solar plus energy storage are not only the most cost-effective options for the Navajo Nation, but they’ll also yield the greatest long-term benefits when it comes to Navajo society and the environment, Horseherder said.

Rewriting Navajo Nation energy policy

TNA participated in drafting the Navajo Tribal Council renewable energy bill. It doesn’t go far enough and it isn’t as specific enough in setting out its goals as TNA would like, but it’s a first step in an ongoing process, according to Horseherder.

The bill proposes an energy transition task force be set up by June 7 and be charged with coming up with recommendations as to how best to boost the Navajo Nation economy and replace the lost jobs, revenues and other socioeconomic benefits NGS and Kayenta yielded. The second main aspect of the bill is rescinding the Navajo Nation’s current energy policy, which, unsurprisingly, is centered on coal and other fossil fuels.

TNA’s persistence helped push federal authorities and NGS’s owner-operators to reconsider their efforts to prolong the power plant and coal mine’s lives. That included the USBR conceding its decision-making role in NGS to the Salt River Project (SRP), one of Arizona’s largest utilities, which has partnered with the Navajo Nation power utility, the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA), to launch the Kayenta I and Kayenta II, utility-scale solar power projects. Combined, the two-stage project will see the deployment of some 50 MW of local, emissions-free, solar generation capacity on tribal land on the Navajo Generating Station site, Horseherder told Solar Magazine.

Charged with providing reliable, affordable electricity for the Navajo Nation, NTUA manages residential and grid-scale renewable energy programs that aim to improve lives, livelihoods and strengthen community across the Navajo Nation, a vast, semi-autonomous territory that spans some 27,425 square miles across northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and northwestern New Mexico.

Last August, SRP, NTUA officials and Navajo Nation community leaders began to break ground on phase two of the Kayenta solar power project. Expected to come online in June 2019, Kayenta II will add 27.3 MW of emissions-free generation capacity on Navajo Nation tribal land, enough to power some 36,000 homes, according to NTUA.

The project is just a starting point for long-term plans NTUA and SRP intend to carry out.

If all goes well, there will be the deployment of as much as 500 MW of renewable energy projects across the Navajo Nation over the next five to 10 years. That’s expected to bring much-needed jobs and revenues. Also, some of the earnings the Kayenta solar and future projects yield are to be used to fund Light up the Navajo Nation, a program being carried out by NTUA and the American Public Power Association. The guiding and informing goal is the electrification of homes throughout the Navajo Nation.

Looking ahead, TNA’s plate is full as it’s participating in efforts to draft a new energy policy for the Navajo Nation, as well as helping secure economic transition funding in the wake of NGS and Kayenta’s closing. It is also sending three participants in its recently launched solar energy education and training program to Solar Energy International in Colorado to be trained and certified as solar installers. The idea is that they will return and not only participate in solar energy project development activities, including training other Navajos, Horseherder also explained.

Converting abandoned coal mines and coal power plants to solar energy farms

“An effort to develop solar at the site of the Navajo Generating Station would benefit from the significant existing transmission infrastructure at the site, and likely is only one of many such opportunities across the Navajo territory. Further, with nearly 70% of the load in the Southwest coming from cities and states aiming to get 100% of their energy from clean sources, the regional demand for clean power is significant,” Uday Varadarajan, a principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), told Solar Magazine.

“However, the scale of these opportunities, likely in the multi-gigawatt range requires a substantial trained workforce, as well as supporting infrastructure to execute their construction at a timescale rapid enough to meet regional demand. Substantial efforts to train, and retrain as appropriate, existing workers at Navajo plants and mines to meet these demands is a near term challenge. Another significant challenge is getting agreement from Navajo grazing-rights holders, local chapters, the [Navajo Nation] council, and developers on a just and equitable allocation of potential royalties and other cash flows from these projects.”

The Powder River Basin spanning parts of Wyoming and Montana, the Appalachian Basins spanning parts of Kentucky, West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania and the Illinois Basin in Illinois and parts of Indiana and Kentucky are the largest coal-producing areas in the U.S., Varadarajan explained. “While there are mines in states neighboring each of these large basins, these are the states where coal either has been, or still is, an important part of the economy.”

That’s the case in southwestern Virginia, where a public-private partnership between nonprofit community development organization Appalachian Voices, the Wise County Industrial Development Authority and Mineral Gap Data Centers is moving forward with plans to develop a 3.5-MW-dc solar power facility on the site of an abandoned coal mine. In March 2019, the AML Pilot program, administered by the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy (DMME), awarded the project USD 500,000 in funding through the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Pilot program. The funds will be used to carry out environmental remediation efforts.

“As Virginia’s first solar project built on an abandoned mine land site, the Mineral Gap Data Center is an important step forward, and shows how communities can be empowered to support job creators while moving towards a cleaner energy future ,” Sun Tribe Solar’s Chief Technical Officer, Taylor Brown, told Solar Magazine. “In the United States and throughout the world, it’s a question of when, not if, communities embrace renewable energy as an essential part of our present and our future; for Virginia, that time is now,” added Chief Strategy Officer, Devin Welch.

“In an increasingly competitive global market, more and more companies are turning to solar as a reliable way to power their businesses, reduce costs, and show their commitment to sustainability. For communities like those in Southwest Virginia, this change is a real opportunity to engage in sustainable economic development, and we’re excited to be a partner in these efforts both today and tomorrow,” Welch said.

Powering data centers and helping reenergize coal communities

Powering its co-location data centers with clean energy has been a goal of Mineral Gap Data Centers from the very beginning, company spokesperson, Marc Silverstein, told Solar Magazine. “In fact, we built Mineral Gap’s infrastructure so we could easily introduce renewable energy into the site. For the past few years, we’ve been exploring different avenues to bring this vision to fruition, in collaboration with Wise County officials and numerous other players. We’re thrilled that we are now able to see this vision become a reality.”

Contributing to the community and helping it recover from the jobs and revenues lost as a result of coal mines being shut down was another major driver for Mineral Gap. “We have always felt strongly about being a part of the Wise County community. Our goal is for our company to be a good community steward, develop projects in the county that will create jobs and financial opportunities, as well as help the environment, all in efforts to revitalize areas that have been negatively impacted by the economic realities of the coal industry,” Silverstein said. “Every new project we bring to Wise helps not only the county but the regional economy as well. We believe the 3.5-MW solar project is the first step in a much larger effort to create more similar projects in Southwest Virginia and positively impact the regional economy.”

Similar initiatives are underway in Appalachia and elsewhere in the U.S., Karen Clay![]() , professor of Economics and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, highlighted in a recent blog post. Among them:

, professor of Economics and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, highlighted in a recent blog post. Among them:

- Project partners recently converted a coal-fired power plant in Holyoke, Massachusetts to a solar power farm. “Partnerships with the city and state provide young employees with job retraining and older employees with early access to retirement savings and pensions,” Clay points out.

- Indianapolis Power & Light Co. has decommissioned four coal-powered units in Martinsville, Indiana and built a natural gas power plant on the sites. That’s created around 1,000 construction jobs and 33 permanent jobs to the community and is expected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 98%, according to Clay.

“These facility conversions could attract younger workers and their families, which would bolster school attendance, support local businesses and preserve many of the plants’ original benefits, but without the pollution,” Clay wrote.

These and other coal-to-solar conversion projects have caught Clay’s attention given previous research she has done regarding the relationship between coal power plants, air, and other environmental pollution, Clay said in an interview. Having spoken to the local congressman, “the biggest issue is jobs. Coal historically has been a big deal in this region [Appalachia, including western Pennsylvania]. This idea that these sites in some cases turn out to be well suited to solar projects seems to be a great opportunity.”

“I think it solves two problems. One is the brownfields problem, which isn’t talked about so much,” Clay elaborated. Reuse of these sites has been limited, and remediation of coal mining and power plant sites can be a very costly proposition that could require years to resolve, Clay pointed out. That said, Clay said she considers coal site-to-solar conversion projects “great opportunity to use for them [former coal mine and power plant sites] for something like solar. Using existing power lines and other, associated infrastructure should be advantageous in terms of project development time, and the infrastructure gets to be reused, which is also a politically sensitive issue,” she said.

Job creation is the second key benefit coal-to-solar projects can convey, Clay continued. “Coal has been an important source of jobs in many communities; shut them down and you could shut down the community, as well,” she said.

Coal mines and power plants have typically employed many more people than the equivalent solar power farm, Clay noted. “It’s not direct, one-for-one replacement in terms of new job creation, but building and operating solar power plants does create jobs,” she said.

All things considered, Clay sees shutting down coal power plants and mines as delivering net, long-term benefits. “You have to get people on board, but I believe re-purposing them is absolutely a win. It addresses local population issues, jobs, and brownfield problems.”

Finding innovative ways to replace coal mines and power plants with solar energy

It hasn’t been involved with a coal mine-to-solar or other renewable energy conversion project to date, but the nonprofit clean energy and energy efficiency specialist, primarily through its Sunshine for Mines program, since 2017 has been acquiring extensive expertise in the field by working directly on similar projects with the mining giant BHP’s Closed Sites team, which manages the mining multinational’s 22 legacy mines in North America.

“We considered both commercially established technologies like solar PV, wind energy, pumped hydro, and lithium-ion battery storage, as well as innovative options including electricity generation from shaft airflow and flywheel batteries. Our team continues to work with BHP on developing the top-ranked sites and advising on project pipeline life cycle from design to commercialization,” Natali told Solar Magazine.

So-called ratepayer-backed bond securitization is one of the new financial tools that many states across the U.S. are considering to boost and support energy-resource transition efforts, Natali highlighted. The guiding and informing principle is to help utilities recover the costs of early coal power plant retirement and the associated loss of jobs and local government revenues.

“Our analysis suggests that for every USD100 million in utility cost recovery financed through securitization, nearly USD6 million could be generated for transition assistance if 15% of the financing cost savings from this mechanism were allocated to transition assistance,” Natali said. “A tool of this type was recently passed into law in New Mexico to address transition needs for the San Juan plant in New Mexico.” From a broader perspective, ratepayer-backed bond securitization could generate roughly USD40 million in transition assistance for impacted communities. Bills with similar provisions are being considered in Colorado, Missouri, Montana, Oklahoma, and Utah, Natali pointed out.